In designing Timeline Game (Timeline for short), a great deal of the inspiration for the mechanics and gameplay came from popular trading card games in the space. In this post, I’ll go through the major influences - what was absorbed into the game, what wasn’t - and why.

Magic the Gathering

Richard Garfield’s Magic the Gathering is known for many things in the trading card game space. For example, the color wheel, the release cadence which sees numerous sets released each year and really the trading card ‘game’ concept itself. Prior to Magic the Gathering, trading cards were collectables for fans of something; cards featuring baseball players, popular characters from media and the like. Garfield’s development of Magic the Gathering made these collectables something one could actually play and do something with.

Game design is something that can be discussed endlessly. One seemingly minor change can ripple out and effect nearly all aspects of play, and for Timeline I made some major changes. I’ll elaborate further on some of these at a later date so that I can keep things simpler here.

The Land System + the Color Wheel

The Land system and the corresponding Color Wheel were innovations that still fascinate both players and game designers thirty years out. To introduce this system briefly, Lands (or “mana”) are what allow players to play cards from their hand. Lands have a corresponding color, typically, and these colors align to certain cards in Magic. A player has to make a choice of which lands to use in their deck and therefore which cards. This system gets very deep very quickly. It achieves a simple goal of not letting every player use the best cards in every set, as they have to opt in to a specific color scheme.

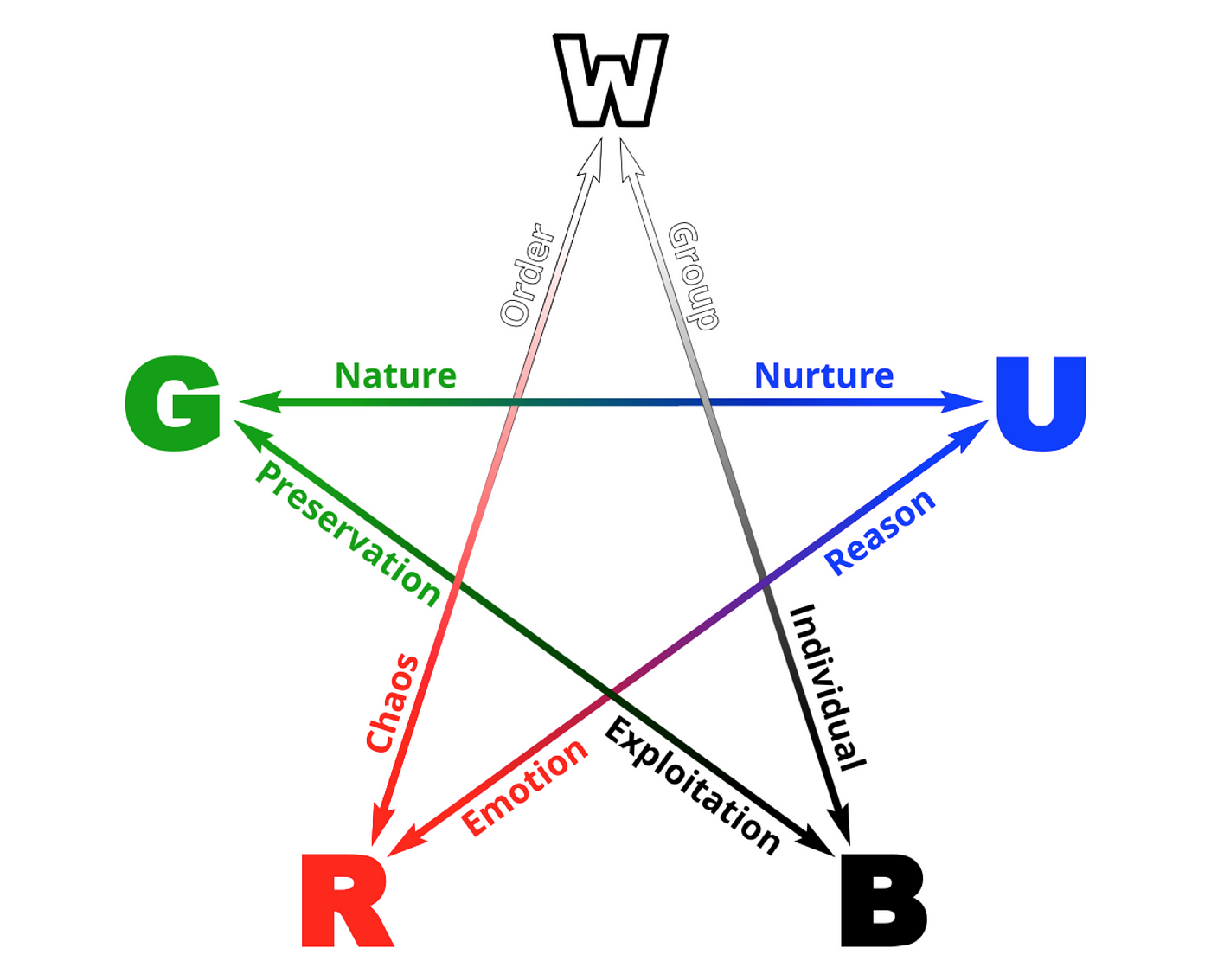

Color Philosophy in MTG

Each color in MTG has a unique identity and corresponding playstyle. These are informative guardrails both for game designers and for players, and they helped inform the design of the factions in Timeline - as will be elaborated on multiple times later in this post. First I’ll briefly talk about what the color system is and how it works.

Red, as a color in MTG, is aggressive. An iconic card for Red is “fireball” (a fireball is also the symbol for Red in MTG) which deals damage directly to the opponent. Many red cards are impulsive or “fiery”; many red cards are relatively cheap to play and allow the player to start taking action immediately.

Blue, on the other hand, has a very different philosophy. Where Red is often “low to the ground” - I.E. relatively easy to play and simple, Blue is operating on a different level and tends to wait and see, or in other words, Blue wants to react. Where Red basically always wants to engage, Blue is a color that likes to choose when to engage - Blue wants to fight on its own terms. Blue cards, for example, often feature flying. Flying cards, when attacking, can only be blocked by other creatures that fly - but they can choose to block non-flying creatures when they attack.

The iconic card for Blue in Magic is “Counterspell”, which I featured in Timeline as “Ratio”.

Counterspells stop your opponent from playing the card they want to play. This defines the reactive playstyle - you can only use Counterspell if you opted to leave your lands untapped on your turn (I.E. you didn’t play many/any cards) and waited to see what your opponent would play.

This is kind of a bluff, as your opponent is aware that you are playing as Blue, and aware that you have lands available to play a Counterspell. They in turn may call your bluff by choosing to play (or not play) a valuable card. If you manage to Counterspell a critical card or two from your opponent, you can neutralize what they are attempting to do and engage on your terms.

Removing the Color Wheel

In Timeline, despite taking a lot of inspiration from Magic, I chose to tweak the land system and remove the corresponding color wheel. These are rabbit-hole style systems that one can easily spend hours optimizing for, and they’re also constraints on the game designer. I wanted to make the game accessible for newcomers. While I opted to remove the Color Wheel outright in Timeline, many of these iconic effects mentioned in the previous section served to inspire cards and abilities. In the case of a card like Ratio, which is Timeline’s Counterspell, without a Color Wheel restricting it to “Blue”, it becomes something anyone can use in any deck.

Rather than use those color wheel restraints, I made factions, many of which interact with each other and encourage you to fill your deck with more cards of that faction. You can mix and match factions like a Magic player might mix and match colors, but you will find that playing away from the natural synergies of the factions will close off some very powerful options from your deck.

There are factions that naturally mesh, like Miladys and Spirits, but there is some room for a Milady and Ape-NFT style deck and whatever you can put your mind towards, although some of the factions have more synergies and internally less synergies with others.

You ultimately have to make a choice about which factions and gameplay themes you want to play towards, as a “anything goes” type of deck - unless sincerely optimized and thought through for a while - will have trouble keeping up with decks that do play towards natural synergies in the factions. This will be touched on again later here.

The Quill Token System + Posters vs Lands

You may be wondering where lands/mana come into all of this. The land/mana system from Magic is great for pacing and many TCGs have used some variant on it. Ramping up from one land to a number of them over time allows the game to start slowly and then erupt with players being able to play more powerful cards once they’ve played some weaker ones first.

The issue with lands in Magic is that they can have some problems of their own, and these problems can make learning the game even harder for new players. Because lands are in the main deck in Magic, you have to balance your deck so that you are drawing a land regularly. If you get unlucky with your land draws, you will be stuck with a hand full of cards you can’t play. Alternatively, if you draw too many lands, you have a ton of lands (i.e. resources to play cards) but not enough cards to play. This is called mana screw and mana flooding, respectively.

Some games, such as Hearthstone, opt to turn this into a more stable system, sacrificing complexity for a more consistent playing experience. I opted into this as well with Timeline, where each player draws one Poster card each turn, from a separate deck of Poster cards, with this stopping once each player has five Posters in play.

In addition to taking out the issue of sorting out your deck with regard to lands and the color wheel, this means you pull a playable card that “does something” each turn.

Without the color wheel and lands within the “main deck”, I layered complexity back into a now-simpler game through the aforementioned faction synergies and a new system revolving around Quill tokens. Quill tokens are taken from a shared pool of fifteen tokens that sits between the players at the start of each game. Each time a player uses a poster card to contribute to the cost of playing any card, they take possession of a Quill token from the pool.

Once a player has four Quill tokens, they can put four back into the pool and “disembody” one of their posters, allowing that poster to contribute two posts to the cost of playing a card, rather than one.

The Quill Pool can be seen on the game board, above, in the top right

This allows a player to reach beyond the “five posts per turn” limit at their own choosing should they want to play more cards than they would otherwise be able to. This system ripples out across the game as it encourages players to include cards that can be played early on and therefore begin stacking as many Quill tokens as they can per turn. As there are only fifteen of these tokens total, there is a hard limit on how many tokens one player is able to stack.

Quill Tokens can therefore be hoarded as a means of keeping tokens and their corresponding effect away from their opponent - by not using them, they are not returned to the pool. Should the pool return to zero, and a player chooses to use four of their tokens (thereby returning them to the pool), upon the next turn it is very likely their opponent will quickly gain possession of all four tokens. It is a type of game within the game which, while relatively simple, can easily decide the outcome of a match and demands attention.

The aim of Timeline Game, and in particular the initial release, was to create an enjoyable foundation of a card game which is engaging and complex, but also simple enough for a beginner to grasp within fifteen-to-thirty minutes of playing. By removing the land system and its corresponding pain points (mana screw/flooding, for example), as well as the color wheel, there are less things for a player to learn, while the Quill system is a simple addition that creates a unique gameplay loop which is foreign to Magic the Gathering and other influences.

Other Influences from Magic the Gathering

I’ve mentioned some of the major divergences and tweaking with regard to the Land or Resource system and the Color Wheel but there are some aspects of MTG influence to discuss first.

The pacing and, essentially, the “spine” of Timeline Game would not exist without Magic the Gathering. While the Land system was stripped down and smoothened out, then further tweaked with the Quill system, much of the gameplay flow mirrors a simplified form of Magic the Gathering.

Hit Points or “Life” Points

Hit Points or “Life”, like in Magic and many TCGs, are also a core part of Timeline. Each player has twenty-five (five more than in Magic) points, and when you have zero, you lose the game. The increase of twenty-five in Timeline from twenty in Magic is a balance decision.

By compressing the total resources (posters) to a cap of five - and since you get +1 to your resource pool each turn guaranteed, unlike in Magic - the game state accelerates and can get out of hand quickly. The Quill system also contributes to this ramp-up.

This is intentional, as Timeline is meant to be accessible and played quickly. The idea is for players to play a number of games back to back, I.E. a best of three or a best of five, and for that to take less than an hour once both players know what they are doing.

With all those factors accelerating play into a more advanced game state compared to most card games, adding five life points makes the game last that little bit longer while still being reasonable.

Creature Types or “Manifestation” Types

Creature Types also behave similarly to Magic in Timeline Game. The only main difference is that in Timeline, creatures and perpetual effects such as Pinned Posts are known as Manifestations, as they are ‘manifested’ onto the field of play by posts from Posters. These manifestations can be searched from decks and there are many cards that interact with certain types of manifestations.

For example, the card Synchronized Crying can only be played if there are three manifestations with the “CRYING” type (typically associated with Miladys) on the timeline under the player’s control.

Additional Inspirations from MTG

Other similarities from Magic include the cadence and phases of play. “Summoning Sickness”, wherein creatures can’t use their abilities or attack the turn they are played, also exists in Timeline.

There is, however, a slight difference in that many cards are balanced around whether their activated abilities cause that manifestation to “tap” for that turn. If they do, it can’t attack or defend until their next turn. There are some variations, where this simply limits a creature from attacking on that turn, while they can still defend on the opponent’s turn.

Additionally, where Magic has more phases in each turn, Timeline has fewer, but in a similar configuration. The main difference from Magic is that after the Combat Phase ends in Timeline, that player’s turn ends. There is no window for taking actions after Combat resolves, prior to the turn ending. You play what cards you can, send your attacks onto the timeline and your turn ends. This is done to simplify game flow as well as to make each turn like one big “post” that is sent in a sequence rather than extended with a second main phase after combat.

Last but not least, there is another mechanic inspired in part by Magic the Gathering; “scheduling posts”, which allows a player to pre-pay some of the cost of a card in advance so as to play it later at a lower cost. This is inspired both by the concept of scheduling posts on Twitter and e-mail but also the “Foretell” mechanic from Magic the Gathering’s Kaldheim expansion. It functions in a very similar way.

Yu Gi Oh, Discarding the Color Wheel, Fusion Monsters + Factions

As mentioned, the Color Wheel is an important part of Magic the Gathering which helps “keep things real” from a perspective of which cards a player can feasibly add to their deck. Without the Color Wheel, players could play all of the best cards basically freely, and the entire point of the Color Wheel and each color’s corresponding gameplay philosophy would go out the window. The Color Wheel effectively makes players choose how they want to play and stick with it.

WIthout the Color Wheel - and drawing playable cards each turn rather than a land every other~ turn - we now have a form of a game that looks similar to Magic in many respects but is in reality quite different. I turned to Yu Gi Oh and their Fusion Monster system in tandem with faction synergies to reintroduce trade-offs to the deck construction process. In doing so, this reinserted an element that is like the Color Wheel, but simpler.

In Yu Gi Oh, Fusion Summons allow a player to play a Fusion Monster card from an “Extra Deck” by activating a set of cards together. For example, by playing the “Polymerization” card - a catalyst card for fusing cards - and two specific creatures, a player can bring out a special Fusion of the two creatures from their “extra deck” on-demand. Because this is a trade of three cards for one (Polymerization + Two Creatures), the resulting card is “allowed” to be very strong from a balance perspective.

Gating Power Behind Combinations

I used the same logic in Timeline Game, but without a Polymerization card as a catalyst. Instead, you have to draw the pieces of the puzzle and play them in order. If you do so, you often get to keep all three. For example, you need one Radbro card and one of five specific Spirit cards to play Radical Spirit.

This can be trickier than it sounds, as the best combination cards can be anticipated, and players have a myriad of “answers” to stop you from achieving this: For example, “Ratio” can be played to stop you from playing a critical piece, your opponent can go on the offensive to force you to block with a critical piece (or to take damage elsewhere as a kind of bluff), a board wipe such as “White Hole” which gets rid of all creatures - or just a card like “Delete” or “Void Nymph” which can remove one chosen target.

If you do get to play these combination cards, they are typically just as susceptible to hard removal such as “Delete” or “Void Nymph” as their puzzle pieces were. These end-result combination cards have a lot of power and synergies, however.

Radical Spirit, for example, with its “Spirit Bomb” ability, can sacrifice one of the Spirit cards used to get it onto the Timeline and deal 3 damage to any target - and also can still attack that turn. Anyone playing around the Radical Spirit card likely has numerous Spirit cards in their deck, meaning Radical Spirit can often go to town on opponents with this ability.

So while these combination-type cards that require set up to play are a “hard” way to gate power in a post-Color Wheel world - “hard” as in, you literally can’t play them without a deck somewhat built around them - there is a “soft” way to gate power in the form of Timeline’s factions. The OG Timeline Game set “Apes vs Miladys” features a few major factions. Going in-depth on those is for another time.

The Milady Faction or “Theme”

To give an example for now, we can look at the Milady faction. There are many Milady-themed cards that support the decision to index heavily on Milady cards during the deck-building process, just as there are NFT-themed cards that support the NFT theme (which many Miladys also qualify in), just as there are Forest Kingdom-themed cards to support that theme, and so on.

This foundational game design encourages players to mix and match only sparingly, and lets game designers for Timeline continue to build on these themes whether through official Timeline Game packs that add additional cards of an existing theme, flesh out or add an entirely new theme, and so on. Derivative packs are encouraged to play with this however they like: they could for example focus entirely on adding new Milady or Ape type gameplay. They could also introduce new factions that only play well with themselves.

In the Milady faction, we can see these synergies immediately through just a few examples. Synchronized Crying, as mentioned earlier, is a powerful card which taps into the fact that there are many Miladys with the crying type. A player could pack their deck full of Milady cards that have the crying type and use Synchronized Crying as a way to paralyze opponents. This in tandem with other umbrella-type Milady cards, such as Milady Village or Work of Truth and Beauty, which both amp up all Milady cards in play, reinforces the theme.

There are also other cards such as Beautiful Friendship which require a Milady type and a Remilio type. This allows a player to modify their deck as they choose, should they want to lean in entirely on the Milady theme, or mix in some Remilios and Radbros to add in some variety. There are also additional subthemes for Miladys such as the Elemental Miladys, or the “Burned” Miladys which can interact with Flame type cards.

Pokémon and MetaZoo

Now that we’ve talked about Factions and Themes, let’s talk briefly about two other games that lent inspiration to game design in Timeline Game.

Pokémon

Pokémon was a great influence. The influence from Pokémon on Timeline Game as an NFT collection, not just a game, deserves an article on its own - but when it comes to gameplay, the simple concept here is that many cards have unique, activatable abilities, just as cards do in Pokémon. While this is something that features in many TCGs, abilities in Timeline are a lot more inspired by Pokémon both in their uniqueness, allowing many cards to serve a specific role or identity within a deck as well the simple fact that they are all “named abilities” and that they are so prevalent.

Like Pokémon, some cards also have multiple abilities. The end-goal was to make the cards both fun to play in the game and rewarding to collect as NFTs. With thoughtful game design and purpose behind each ability, cards have a character to them, such as Radical Spirit and his Spirit Bomb ability, which fits the idea of a Remilio/Radbro who is not only spirited from his Milady roots but chaotic and dangerous, which stems from the Remilio/Radbro side.

MetaZoo

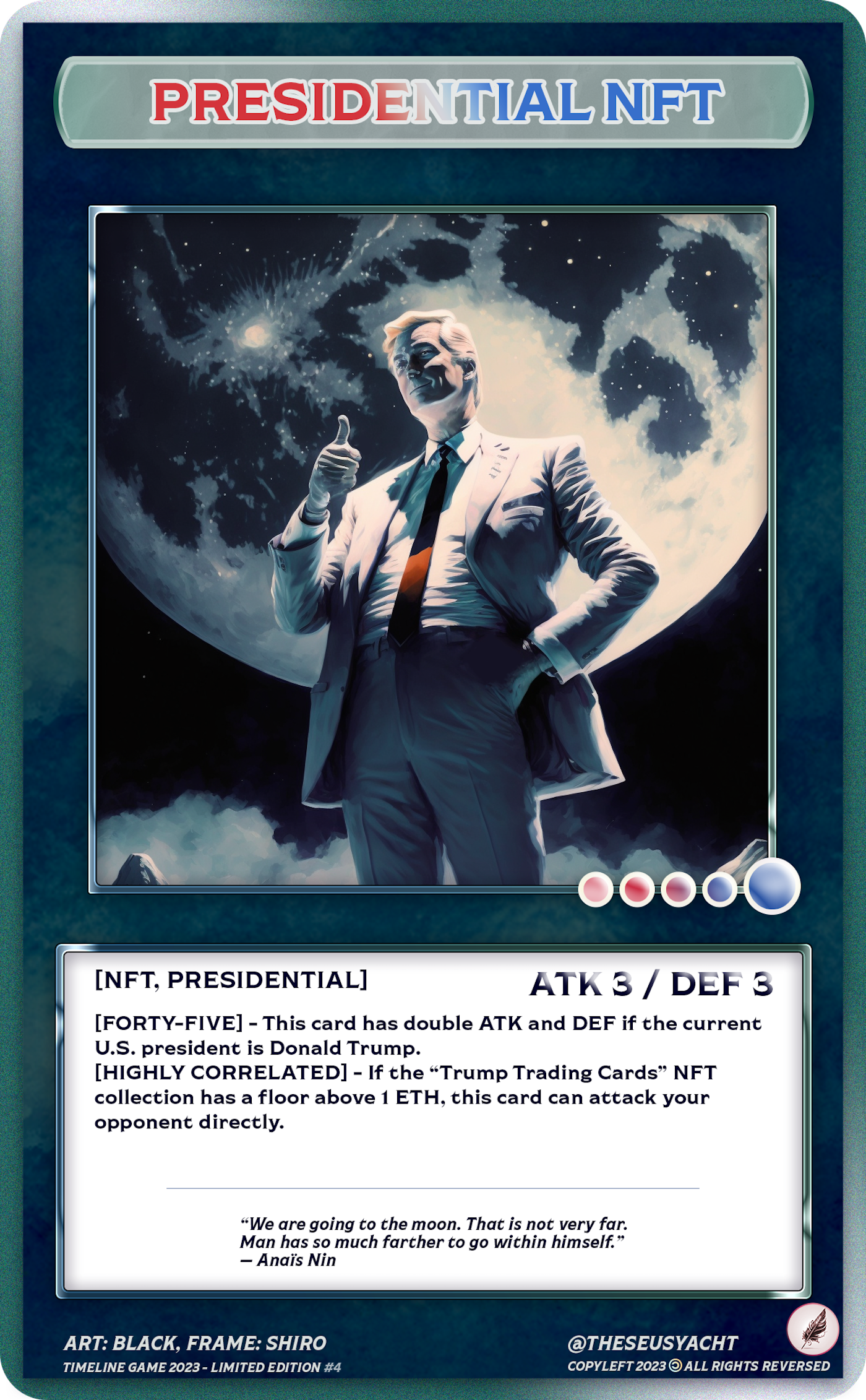

Last but not least, MetaZoo, a new entrant into the TCG scene, provided an inspiration in the form of “fourth wall”-breaking effects. These are abilities and effects which tie in to something from outside the game. This was a natural alignment for Timeline, which is itself a game that takes inspiration from the digital timeline or “real world” and converts it into TCG form. It only seemed appropriate to include cards that are stronger at, for example, certain times of day.

There are other examples of this, such as the Presidential NFT card, which has double ATK and DEF if Donald Trump is the current U.S. President, as well as being able to deal damage directly to opponents if Donald Trump’s Trading Card NFT collection has a floor price above 1 ETH. This meta effect allows the card to reflect reality, Trump has much more presence and power on the Timeline in a real sense, in the real world, when he is the current sitting President.

Similarly, this card as a Donald Trump “NFT” type card, has more oomph if the corresponding real NFT collection is in a strong position.

That does it for these Notes on Game Design - I know it was a long one, so thank you to anyone who read~